In this reflection, I’ll assemble some preliminary thinking I’ve been doing on the relationship between efforts to reduce homelessness and to reduce the footprint of the criminal legal system.

I have no expertise in housing policy, but am persuaded by the analysis that “homelessness is a housing problem” rather than primarily a drug use or mental health problem, which you can read a lot more about in this excellent post by Noah Smith. This means that where housing is expensive, you’ll find more homelessness (e.g., California, but not so much in Texas or West Virginia). In California, where the state has increased its spending on homelessness by 9x in the past 5 years to a height of $4.7 billion in the latest budget, and where localities have successfully housed tens of thousands of people in recent years, the problem is still getting worse. Month to month, the number of newly homeless people continues to exceed the number of people that the system can house. (For a thorough background on CA approaches, I really recommend this article.)

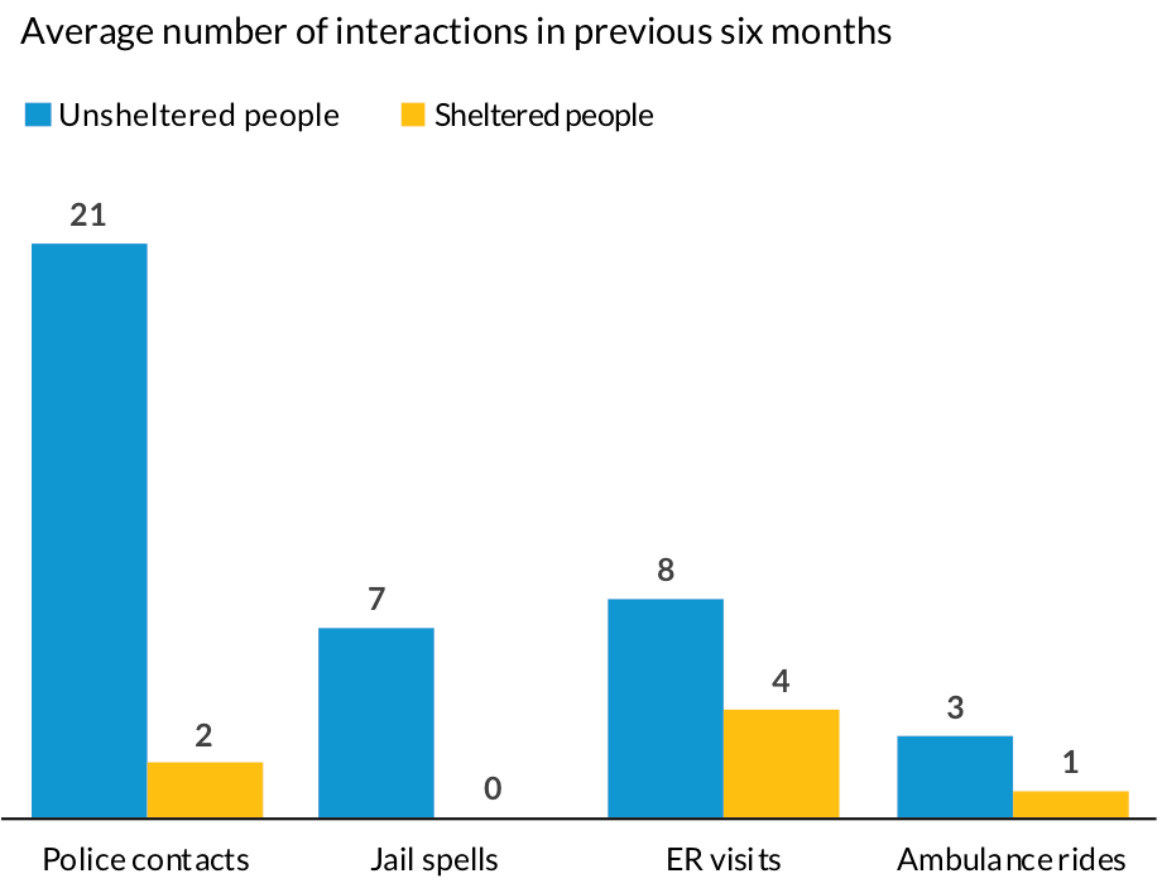

Meanwhile, a recent brief by Partners for Justice details the many research studies finding strong connections between homelessness and the criminal legal system, with causation going both ways. Unhoused people are extremely vulnerable to criminalization, and having a criminal record can make it very difficult to find housing. (Incarcerated journalist John Lennon recently wrote a great piece on the latter.) The brief contains many more interesting and worthwhile examples of this intersection from a sociological perspective. You should also check out the Prison Policy Initiative brief focusing on homelessness among formerly incarcerated people, and the great report from the Urban Institute explaining the “homelessness-jail cycle.” Here’s a chart included in both:

In some of these cases, people are ending up in jail or prison for reasons that are also driving their housing insecurity. However, keeping in mind the proposition that homelessness is a housing issue, not one primarily driven by drug use or mental health challenges, I think it’s likely there are a significant number of people for whom incarceration is the proximate cause of homelessness, and that absent incarceration, they would still be housed. Once they become homeless, they are much more likely to pick up additional criminal convictions, per the Urban Institute:

Moreover, there are people who don’t have a criminal record who are homeless as a direct result of an arrest. How so? The economic instability triggered by an arrest / jail stay impacts not just the person arrested, but their entire housing group, especially in places where rents are so high that even a temporary loss of income (such as a few days out of work if someone is sitting in jail) puts a family on the fast track to eviction.

If that’s right, then states like California that are investing heavily in reducing homelessness could get a lot more bang for the buck by reducing the number of people being pushed into homelessness by excessive arrests and jailing. That would allow them to get ahead of the problem (by avoiding so many people becoming newly homeless while they are putting together housing as fast as they can), instead of falling increasingly behind.

Unfortunately, the politics of homelessness and crime drive major cities in exactly the opposite direction, increasing arrests which in turn will drive more homelessness. Why? Because an increase in the number of visibly homeless people in urban centers often fosters a reactionary politic. Mayors and other electeds rush to show they are ‘cleaning up’ the problem to pacify frustrated residents.

The quickest way to do that is to try to arrest the problem away, which of course does not work, as arresting a person (causing them to lose valuable possessions, including critical identification papers), makes their situation even more precarious and harder to escape. Visible homelessness can also foster a more general sense of rising disorder that becomes linked to crime in the public mind, leading to calls for more arrests and harsher punishments to deter crime, even though that doesn’t work either. Indeed, reducing misdemeanor arrests seems to be one key to reducing crime, which is hard for an anxious and fearful public to accept. It’s a nested set of misattributed causes and effects, with fear and anxiety at the root.

Plans are in the works to invest in future research that keys into the question of how frequently an arrest or other court system involvement is the proximate cause of a person or family becoming homeless. If that number is as high as I suspect, then perhaps we will see a more integrated conversation at the highest levels of government in places like California and New York between housing policy and jailing policy.

Curious to see a self-proclaimed Reagan rehabilitator like Noah Smith weighing in on this. The great criminologist Elliott Currie points out that low-income housing programs were "slashed more deeply than any other federal activity" from 1981-1989, by 75%.

Great analysis! Any leads on folks on the narrative side of things holding this analysis to move public opinion effectively?