Jail facts

Roughly 550,000 people are in jail after an arrest on any given day in the U.S. Over 80% of those people are waiting trial or a plea bargain on their charges - they are legally innocent, but are held because they can’t make bail or other conditions (see PPI's awesome charts). Even a short jail stay can destroy a person’s life — impacting their family, their children, their ability to keep a job and home, not to mention the lasting trauma of being held in a noisy, dangerous, terrifying place. Racial disparities are huge — if you have any kind of privileges or resources to draw on, you’re going to use them to avoid sitting in a jail cell for weeks while the city figures out what to do with you. Who’s left? The poorest people in the community, who are disproportionately Black and Brown. Not only that: the cost of holding a person in jail can be enormous. Can you guess what a New York City jail bed costs per year? I bet you can’t. But come up with a number and hold it in your mind. Now here’s the answer: five hundred and fifty six thousand dollars - per person. I highly recommend you check out the stats in this document to learn more about that number. Truly, WTF.

OK, so we don’t want people stuck in jail just because they’re too poor to pay, that much seems clear. We don’t want to be monsters throwing people into torture and death chambers (16 people died on Rikers in 2021, for example, and many more were injured and/or traumatized by intense violence by guards and other prisoners). And the budget numbers are simply wild. Yet many get stuck on the following question: if we’re not putting someone in jail after an arrest, what do we do instead? If there’s not going to be a jail intervention, what should the not-jail intervention be? This is a false choice.

Remember, we are mostly talking here about people who are legally innocent (though I don’t think people who’ve been convicted of crimes should be put in torture jails either). Putting someone on supervision, which means regular meetings with a probation officer and/or being forced to wear and pay for an electronic ankle monitor, is oppressive and hard to justify if they haven’t been convicted of anything. Those bringing a softer touch than surveillance, when asked “what else” other than jail, may say something like “holistic services,” where a person is compelled to get some kind of help. We often hear about unmet needs, and wrap around approaches, etc., all under the cloud of coercion.

Indeed, the best intervention in many cases is to do nothing instead of jail — it turns out that almost everyone does fine, returns to court, and doesn’t get into any trouble in the meantime. It turns out that people want to return to court and get their cases over with, and if they’re missing court it’s because they didn’t get the notice, or couldn’t get transportation, or were in the hospital at the time, etc. To the extent services would be beneficial, they should be provided freely to the community, rather than limited as a condition of coercive surveillance.

Yet this approach can be hard for many to accept, including many organizers and advocates who are working for pretrial reform. There is unfortunately a thin line between advocating for people who are arrested to receive helpful services in the community, and advocating for the expansion of oppressive mass surveillance. And to be clear, mass surveillance directly feeds into mass incarceration, since probation and other systems (including various community services, which ‘report’ people to state agencies for breaking rules!) are set up to create a constant cycle of rearrest, financial penalties and entrapment.

What are some ways to give money to reduce all this gratuitous jailing? (1) fund grassroots organizing groups that are pushing for more people to be free before trial without adding more supervision; (2) fund services that increase freedom (rather than adding more traps for people to get sent back into jail), such as: creating and growing more defender offices to make sure lawyers are there demanding release; increase the availability of housing; and back guaranteed income projects. In other words, to the extent we are looking at funding services in connection with reducing pretrial incarceration, the services should be ones that directly lead to releasing people or not arresting them in the first place.

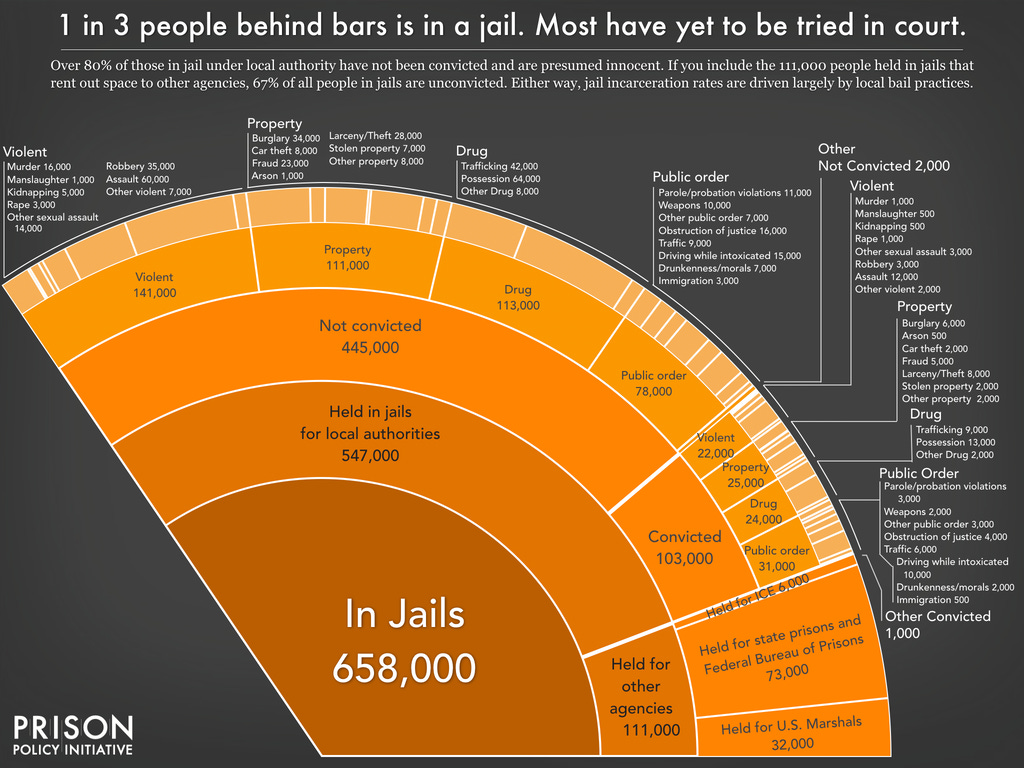

Bonus: here is a beautiful chart by the Prison Policy Initiative, which has so many great reports on CJ data — look through their website sometime and be amazed. They are also a great organization to give money to!