Just Impact reflections 3.16.22

Prosecutor powers

John Pfaff has a new piece exploring the somewhat weird phenomenon in cities like Philadelphia, Chicago, and San Francisco, where voters have been electing quite reform-minded DAs while at the same time electing quite regressive mayors. This is unfortunate, since the mayors have a lot more relevant tools with which to solve problems like homelessness and poverty that are currently shoved in the crime bucket, yet they are looking to these DAs to solve those problems with jail and prison. Meanwhile the DAs, drawing on years of experience, know that their tools aren’t adequate or appropriate to solve those harms. There are several paradigms here that need to shift at once, all in the context of factually challenged political discourse.

Polling crime perceptions

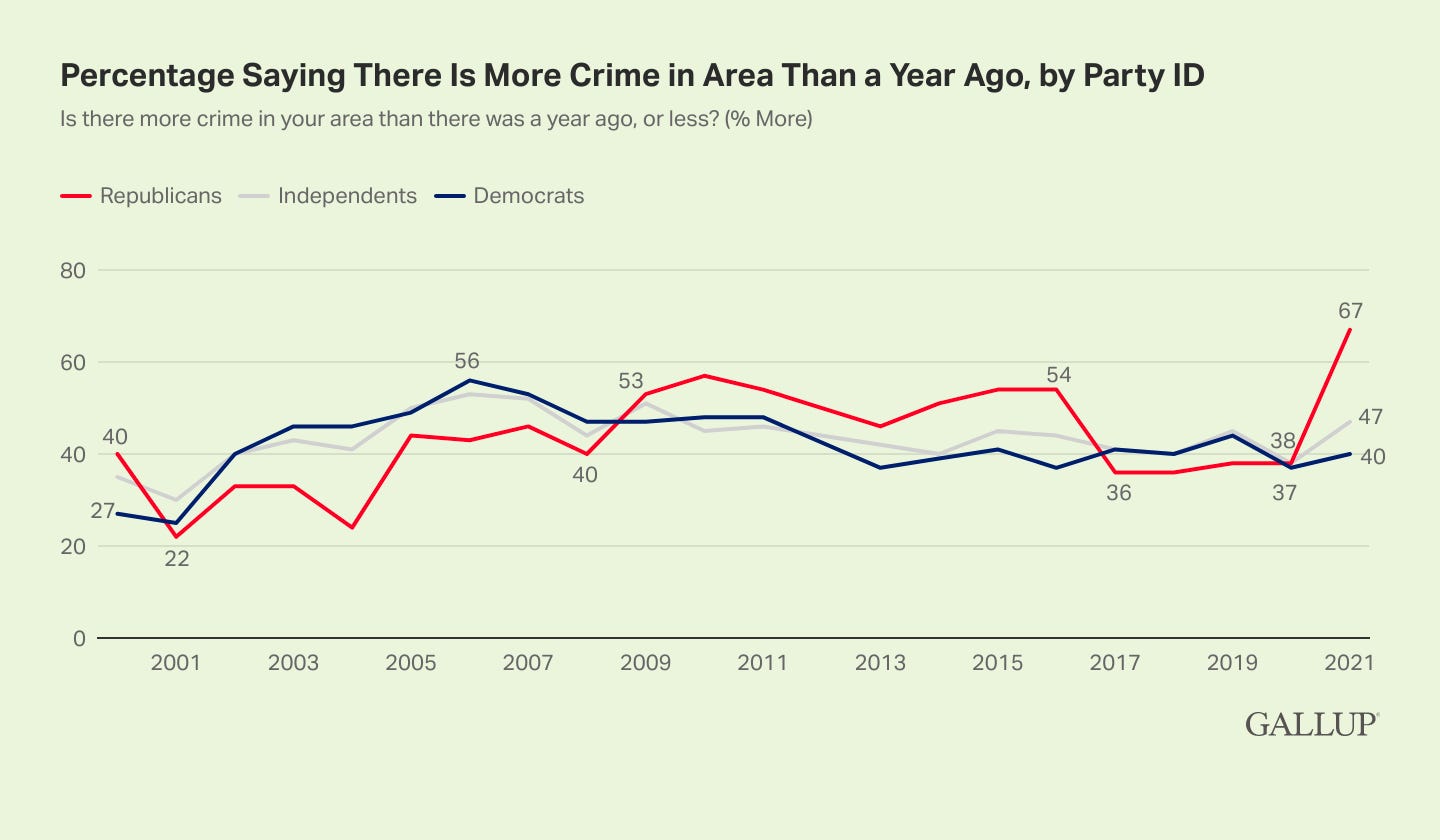

Where do you think perceptions of rising crime have increased the most in the past year? If you said cities, you would be wrong! According to the most recent Gallup polling (from 2021), there was a steep rise in the number of people who said that crime went up in the past year in their area, and it was almost entirely driven by white Republican men in rural and suburban areas. This fits with the longstanding pattern, evident in the chart below, that people’s perceptions of crime are surprisingly dependent on whether the sitting President is of their party or not. As you can see, when a Democrat is in office, Republicans are more likely to say crime is going up, and when a Republican is in office, Democrats are more likely to say crime is going up. Since Biden took office, the rise in Republican crime fears has been unprecedented in the past 20 years.

But what does an assessment of crime going up in the past year in your area have to do with who’s in office? It’s weird that there’s such a strong pattern here. I attribute this to ‘fear of crime’ really being about several things, one of them being a generalized social and political anxiety. What this means is that people working on reforming the torturous, harmful, and wildly expensive prison and jail systems are held responsible for soothing fears that have nothing to do with actual crime. That makes the job pretty difficult. Of course, there are real crime problems that need solutions, but it’s hard to get to those when the media is breathlessly reporting on opinion polls about crime as if they were facts, as we see regularly these days.

Defenders

One of the most obvious ways to prevent more people from going into jail and prison is to improve and strengthen public defense. Public defenders represent over 80% of people charged with crimes. When they’re resourced properly, they have a lot of leeway to create solutions for people in crisis. The better the defense, the more charges get dropped, the more people are allowed to serve time in the community instead of in a jail or prison, and the more the punishment is right-sized to the crime.

So why don’t we hear more about funding criminal defense as an important CJR funding strategy? Because it’s a government service provided to millions of people spread across thousands of publicly-funded state and county agencies, which have uneven access to resources. Moreover, since over-criminalization and over-prosecution are widely-distributed phenomena, investments need to fuel decentralized work in order to be effective at scale. I note that there are several offices that recruit private resources to provide high quality “holistic” defense, which is a good thing, but not scalable.

In response to these conditions, some organizations are working to promote local-level advocacy to increase government investment in defense, while also funding the kinds of training and support that can give motivated defenders a leg up in their work. Keep your eye on these groups working in multiple jurisdictions to support defenders with training and other advocacy-enhancing supports: Gideon’s Promise; the Black Public Defenders Association; Zealous; and Partners for Justice.