Update on trends in the criminal legal system

I missed this June report from Vera providing data comparing 2019 to 2022 prison and jail populations. While there’s still a huge amount of unnecessary incarceration, and things are getting especially bad in states like Texas, I want to take a minute to appreciate some points of progress. The first is the trend over the past few decades:

“States in the Northeast have reduced their prison populations by an average of 43 percent since their peak. Connecticut, New Jersey, and New York have all reduced their prison populations by more than 50 percent from the respective peaks in 2007 (Connecticut) and 1999 (New Jersey and New York)... Massachusetts’s prison population is now almost half the size it was at its peak in 1997.”

In the midst of really difficult, long term work, it’s helpful to be reminded that long term progress really is possible. The short term is even more striking:

“Between 2019 and 2022, the number of people incarcerated in state and federal prisons in the United States declined by nearly 15 percent, from roughly 1,428,226 people to about 1,222,367… This translates to… 212,000 fewer people incarcerated in state prisons across the country in 2022 than in 2019.”

The big factor here is COVID, which forced systems to radically change how they were operating. Around the country, advocates, organizers, and technical experts were poised to assist systems to take the opportunity to adjust their policies to meet the dangers of the pandemic, but also to get out of longstanding ruts that were inflating incarceration. Nationally, the incarcerated population plummeted by about 20% at the start of COVID. The numbers have come back up, but are still substantially below 2019 levels.

It remains to be seen whether numbers will continue rising to their 2019 levels, or whether the system numbers will restabilize at a lower rate. Prison population numbers are to a significant degree elastic in response to short term policy choices, such as whether to send people back to prison for technical violations of parole and probation (such as missing meetings, bad drug tests, inability to pay steep fines and fees, and failure to get a job), and whether or not to hold people in jail before trial who can’t pay bail (being held before trial is highly predictive of whether the person will be convicted). Talking points propounded by the Heritage Foundation and Fox news are pushing messages, picked up by media and elected officials and candidates, that crime is rampant (it is not; see below). As a result, legislators may be susceptible to passing laws to increase incarceration, or reversing reforms that have been working to keep people out, and system actors like judges and probation officers may follow the momentum to increase harshness.

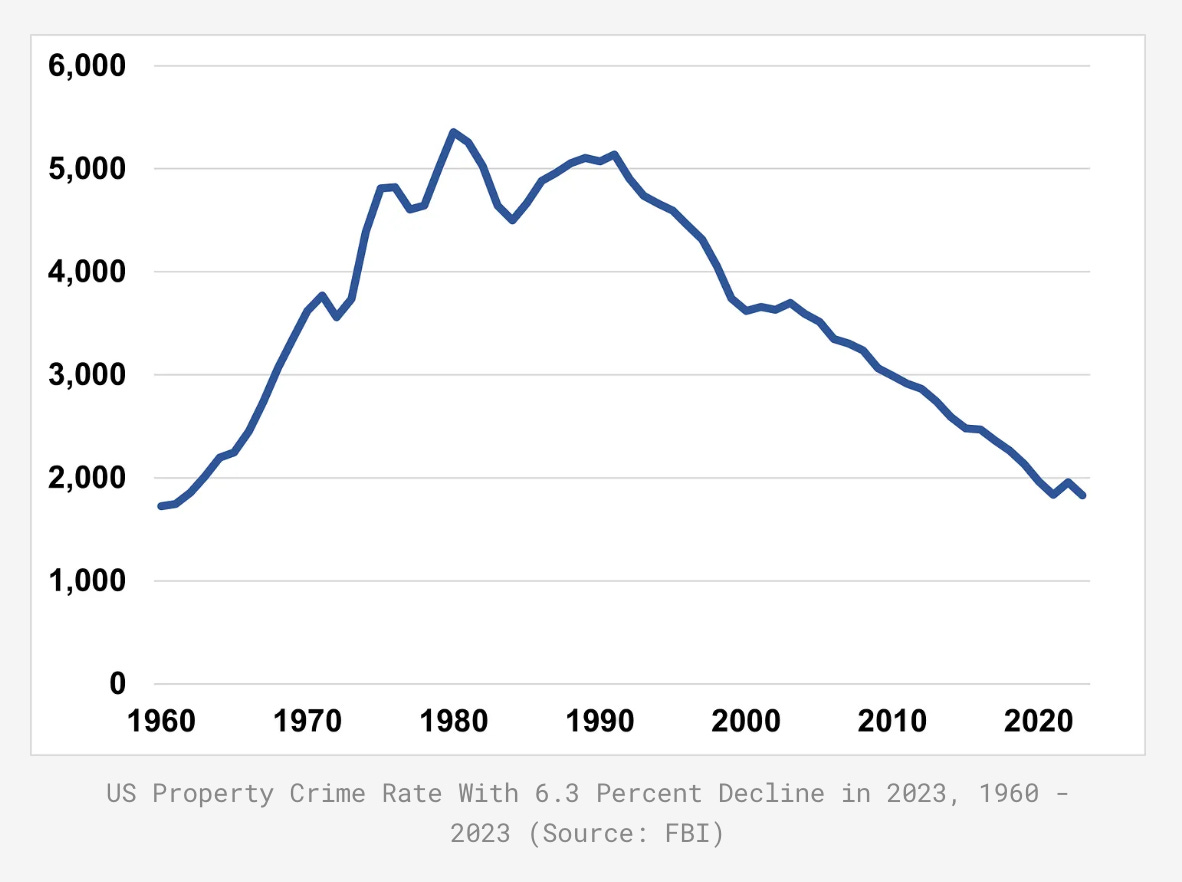

The most important trend to note at the end of the year, in direct contradiction to the above messages, is that crime is falling dramatically - a “peace wave” as the Atlantic calls it. If the current trend continues through the month, America will have achieved the lowest violent crime rate since 1969, and the lowest property crime rate since 1961, according to analysis by criminologist Jeff Asher:

NBC asked Asher for an explanation of the major disparity between these numbers and recent polling, which shows that Americans think crime is rising. His take: “I think we’ve been conditioned, and we have no way of countering the idea [that crime is rising]. It’s just an overwhelming number of news media stories and viral videos.”